Howells - Requiem - Music Web International

> See recording details...I’d scarcely sent off my review of the fine recording of the Howells Requiem by Paul McCreesh than this new Hyperion disc arrived on my doormat. By an odd coincidence both works were recorded in the same venue: the Lady Chapel of Ely Cathedral. Interestingly, both recordings are produced by the same man, Adrian Peacock, though different engineers were employed on each project.

I’m not sure I’ve heard A Hymn for St Cecilia before. Certainly it was something of a surprise. I’d half expected something similar to Britten’s piece of the same name; a mellifluous work for unaccompanied choir. What we get, in fact, is a fairly sturdy hymn tune with organ accompaniment. Annotator Paul Andrews says that the tune is one of the composer’s most memorable. I don’t think it matches Michael– of which more later – in that regard, not least because it’s one that undulates its way through lengthy verses, but there’s no doubt it’s a very good tune. The hymn was commissioned in 1960 by the Worshipful Company of Musicians – Howells was honoured as Master of the Company in 1959-60 – and the words were written specially by Ursula Vaughan Williams.

Salve Regina is better known, though it only came into the repertoire relatively recently. It was one of four anthems written for R.R. Terry and the choir of Westminster Cathedral to sing at Easter 1916. Only two of the anthems survive and what I didn’t know until reading Paul Andrews’ very good notes was that this came about only because members of the cathedral choir transcribed them. We’re lucky to have this beautiful, prayerful setting, then, in which Howells’ penchant for aching, rich harmonies and full choral textures is already evident; and we’re also lucky to hear it in such a fine performance as this one from the Trinity College choir.

Between 1918 and 1975 Howells composed no fewer than twenty settings of the Evening Canticles. The set that he wrote for Gloucester Cathedral was the sixth chronologically, coming a year after his celebrated Collegium Regale set. Howells generally knew well the churches for which he wrote Canticles – and their acoustics – and he could have known none better than Gloucester Cathedral where as a boy he had been an articled pupil of Sir Herbert Brewer. These fine settings of the Magnificat and Nunc dimittis are perfectly imagined for the magnificent spaces and resonant acoustic of Gloucester Cathedral. In particular, the fervent, majestic doxology, which concludes both Canticles, swells in splendour, though the music then subsides to a quietly reflective close. The beautiful Nunc dimittis apparently left the then-Dean of York, Eric Milner-White, “in inward tears for the rest of the day” after he first heard it. The St Paul’s Service was written five years later and Paul Andrews comments that here Howells seems to be “at his most confident and optimistic”. One wonders whether he could have done full justice to the task of composing for the vast spaces of St. Paul’s had he not been in such a frame of mind. Like the Gloucester Canticles, these St. Paul’s pieces, which are even finer, display Howells’ feeling both for place and for language. The Magnificat is a tremendously confident piece and, as Andrews justly observes, the doxologies that end both Canticles, “sweep all before them”. The Nunc dimittis is more subdued and reflective yet rises inexorably to a climax at ‘to be a light to lighten the Gentiles’. Stephen Layton and his choir rise to the occasion in both sets of Canticles, giving masterly accounts of them.

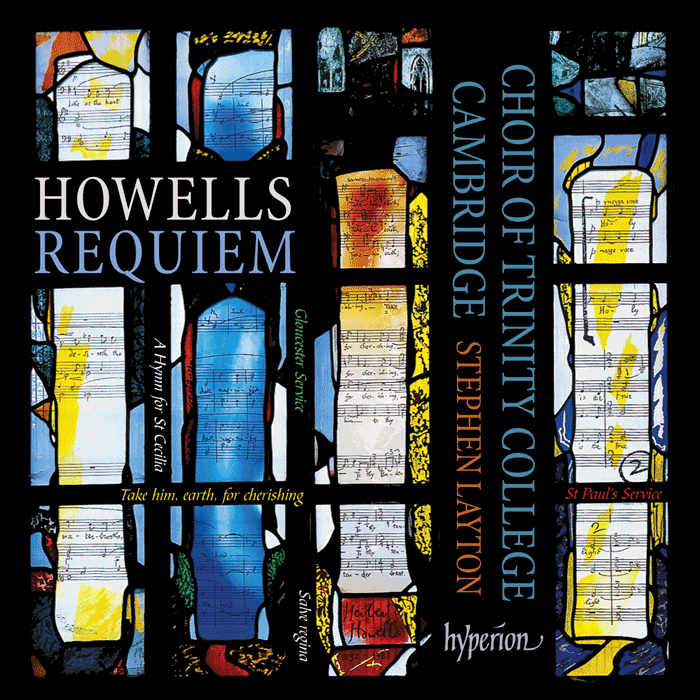

The hymn All my hope on God is founded is an ideal way to finish Evensong. The tune is a splendid one, typically English in its sturdiness and confidence. Though named in memory of Michael Howells when published in 1936, the tune was written while he was very much alive – and, apparently was composed, quite literally, over breakfast one morning. In this performance we hear a last verse descant by John Rutter, which is very effective. It’s very appropriate that Rutter should be linked with this hymn for he is a longstanding admirer of Howells. The cover of this CD reproduces the splendid Howells Memorial Window in Gloucester Cathedral. That was dedicated at an Evensong during the 1992 Three Choirs Festival. I had the good fortune to be in the congregation for that service and to hear the first performance of Rutter’s fine Hymn to the Creator of Light, written for the occasion.

Take him, earth, for cherishing is one of Howells’ most searching compositions. As is well known, it was written, to a commission, for a Washington memorial service for President Kennedy on the anniversary of his assassination. However, Paul Andrews points out that fragments of the music date back as far as 1932. At one point Howells planned to set some or all of the words that ended up in Take him, earth, for cherishing as part of Hymnus Paradisi. He didn’t do that but I think I’m right in saying that the first two lines of Take him,earth, for cherishing, in Latin, are inscribed at the head of the full score of Hymnus. I find that the motet makes a wonderful prelude to hearing the Requiem, even though stylistically Howells developed quite a lot and his musical language became even richer, between 1932 and 1964. The performance on this disc is a deeply satisfying one.

The Requiem is the major element in Stephen Layton’s programme. It lay unperformed for many years until 1980 and achieved its first recording, I believe, in 1983, when the Corydon Singers set it down for Hyperion. That fine recording is still in the catalogue (CDA 66076). I know of at least two subsequent recordings; by the Vasari Singers (1994) (review), and by St. John’s College, Cambridge (1999). When the score was first released for performance it was thought that the work was a direct response to the tragically early death of the composer’s son, Michael, in 1935. However, in his notes Paul Andrews correctly says that the late Christopher Palmer established that the Requiem dates from 1932. In fact, if I may expand a little on what Mr Andrews says, in his book Herbert Howells. A Centenary Celebration(1992) Palmer quotes a letter that Howells wrote on 13 October 1932, in the course of which he says:

“I’ve added a complete new short work to my holiday list – a brief sort of ‘Requiem’… I began flirting with the idea on Sunday. I finished it yesterday and am copying it out. It’s done specially for King’s College, Cambridge.”

Since 13 October fell on a Thursday in 1932, this would imply that Howells composed this work in a mere four days, which seems astonishing for so profound a piece. Whether the (unsolicited) work would have been taken up by King’s is a matter for speculation. What is certain is that following Michael Howells’ death his father incorporated music from the Requiem into his radiant masterpiece, Hymnus Paradisi and then locked both scores away from public view for many years.

In my opinion there are few modern English a cappella choral works that match the Howells Requiem – the Vaughan Williams Mass in G Minor is on the same lofty level. Paul Andrews describes it as “a wonderful heart-rending work of searing beauty” and that description surely goes to the heart of the matter. Interestingly, Howells appears to have taken as his structural model a little-known work by one of his teachers, Walford Davies. His A short Requiem(1915), also for unaccompanied choir, sets several of the same texts that Howells selected. I’d be interested to hear that piece one day but not, I think, in proximity to the Howells work since I can’t believe it could match the eloquence and radiant beauty of Howells’ incomparable setting.

The performance on this disc is simply wonderful. Howells’ long, arching phrases and rich textures are flawlessly executed and the music is sung with evident feeling. The performance reaches its zenith with a moving and deeply felt account of the last movement, ‘I heard a voice from heaven’, which is the one most closely linked to Hymnus Paradisi. Here, and elsewhere, the solos, taken by choir members, are beautifully delivered.

It’s been fascinating to go back to Paul McCreesh’s very fine performance and to compare it with this Layton account. The first thing that I noticed is that McCreesh takes 24:02 for the whole work whereas the Layton reading lasts for 20:18. Layton’s overall timing is pretty close to the recordings by Matthew Best and the Corydon Singers (20:03) and Jeremy Backhouse and the Vasari Singers (20:31). At the opposite end of the scale, Christopher Robinson and St. John’s College take just 16:41. So, it would seem that Layton is in line with what I might call the “consensus view” of the piece. The main differences of timing between McCreesh and Layton lie in three of the six movements. In the third Layton takes 3:45, while McCreesh takes 4:53. The fifth movement takes 3:37 with Layton but 5:08 with McCreesh and in the last movement the two conductors take 4:30 and 5:38 respectively.

One explanation may be that McCreesh takes longer simply because he can. He has a choir of experienced professional singers whereas Layton’s choir, marvellous though it is, comprises students. It’s noticeable also that McCreesh’s choir is smaller – 7/5/5/5 against Layton’s 13/9/9/9; this may give McCreesh a greater degree of flexibility in drawing out the extended lines. However, I suspect that the main reason that McCreesh is more expansive is simply that he feels the music that way. Both readings are very expressive and I haven’t modified my admiration for the McCreesh reading at all. However, having had the opportunity of comparing the two performances side by side – and it’s especially interesting to hear each movement in one performance followed by the other – I think that the greater degree of fluency and the rather more natural feel of the Layton reading wins the day. Oddly, I felt that Layton is able to achieve an even greater degree of intimacy through adopting slightly more flowing speeds. As I said earlier, both recordings were made in the same venue and by the same producer. I have the impression that McCreesh’s choir sounds to be slightly more distant from the microphones than Layton’s but, paradoxically, there seemed to be just a bit more resonance around the sound of the Cambridge choir. The sound on both recordings is excellent and just right for the music.

The sound throughout this Hyperion release is first class, both in the lovely, intimate Lady Chapel at Ely and in the larger acoustic of Lincoln Cathedral. I wonder why they didn’t simply move out into the main building of Ely Cathedral for the accompanied pieces. The documentation is as good as the performances and sound: Paul Andrews has contributed an excellent essay on the music. Incidentally, I’ve commented on the pieces in the order in which I found it most satisfying to listen to them. After the Requiem I’m not sure that one wants to hear a forthright hymn tune.

I’ve yet to be disappointed with a recording by Stephen Layton and Trinity College Choir. This Howells disc shows them at their very best. It’s glorious music, superbly performed. This is, in short, a most distinguished release.

John Quinn

Hyperion Records CDA67914