Bach - Christmas Oratorio - Voix des Arts

> See recording details...Few compilations of repurposed music have been as embraced by musicians and listeners as Johann Sebastian Bach’s Weihnachtsoratorium has been in the years since it was reintroduced to audiences in 1857. Created for celebration of Christmas-season liturgies at Leipzig’s Nikolaikirche and Thomaskirche in the winter of 1734 – 1735, Bach’s score made use of music composed for several secular cantatas and two of his Passion settings, perpetuating a standard practice for the composition of large-scale works that was frequently employed both by Bach and virtually all of his contemporaries. Though musicologists of years past suggested otherwise, it is clear from the carefully-constructed dove-tailing of key progressions and musical forms that Bach conceived the Weihnachtsoratorium as a single work in six parts rather than a series of cantatas with incidental seasonal associations. What cannot be known is whether Bach, much of whose music did not circulate widely during his lifetime beyond the artistic centers in which he worked, had any expectation of the preservation and future performance of his oratorio for Christmas 1734. Like the scrapping of the original plan to dismantle the Eiffel Tower after its service in the 1889 World’s Fair, however, the notion of disassembling such a monument in Western sacred music now seems criminal. The stylistic unity of the individual parts is a tremendous testament to Bach’s genius for the complex mathematics of sustaining thematic elements across wide musical landscapes. In this regard, theWeihnachtsoratorium is hardly less impressive as a continuous pursuit of dramatic and musical threads from start to finish than Wagner’s Der Ring des Nibelungen; considerably smaller in scale, of course, but also filled with some of its composer’s most memorably beautiful music. No music in the Western canon more exhilaratingly conveys cathartic joy than the festive strains of ‘Jauchzet, frohlocket, auf, preiset die Tage,’ proclaiming the birth of the Savior into an oppressively sinful world, and even among Bach’s works there are few evocations of hope and rapt spirituality more affecting than ‘Fallt mit Danken, fallt mit Loben.’ The disparate origins of the individual cantatas notwithstanding, there is not one page of theWeihnachtsoratorium that does not contain music of exquisite quality. It is the kind of score that inspires insightful musicians to give of the best of which they are capable, and the artists assembled by Hyperion for this recording devote their collective intelligence and musicality to giving a remarkable performance of Bach’s music. Many excellent performances of the Weihnachtsoratorium have been committed to disc, but the best among them can only match the high standards achieved in this recording: these are artists who both understand and love the music of Bach, and their efforts welcome the listener, regardless of his beliefs, into the true spirit of the Christmas season.

The inviolable heights of excellence that Bach maintained throughout his music for the Weihnachtsoratorium are all the more apparent in a performance as consistently accomplished as this one, and much of that consistency can be attributed to the unerringly stylish leadership of Stephen Layton. Maestro Layton here proves anew the depth of his instincts for Baroque music, whether it was originally composed for Leipzig or London. Though a true masterpiece, the Weihnachtsoratorium is not a work that is immune to ill-conceived or indifferently-executed conducting: the subtle shifts in mood from the extravagantly celebratory to the raptly contemplative are far more effective when a conductor is attentive to the musical means employed by Bach to convey them. In terms of both essential musicality and complete comprehension of the ways in which Bach propels the Christmastide narrative with distinct rhythms and key progressions, Maestro Layton’s pacing of this performance wants for nothing. The critical differentiations of instrumentation among the six parts, defined by alternating deployments of trumpets and woodwinds, are deftly handled without the broader architecture of the work being obscured. Unusually for a performance of any of Bach’s oratorios, there are no tempi that seem anything but ideal for the music. Integral to the success of Maestro Layton’s conception of the score are the marvelous performances by the Choir of Trinity College, Cambridge, and the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment. Producing precisely the weight of tone that fills Bach’s choral music without danger of either the anemic sounds of the recently-fashionable single-voice-to-a-part practices or the elephantine travesties of Victorian performances, the Trinity College choristers sing in carefully-inflected but natural-sounding German. Drawing upon the best elements of the legendary British choral traditions, the blend achieved by the Choir is excellent, with ‘spotlighting’ of individual voices within the choral textures completely avoided. The purity of boys’ voices is suggested in the sopranos’ singing, but the absolute security of intonation and wider range of dynamics possible with adult female singers are especially welcome in this music. Ever one of the most elegant period-instrument bands, the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment lend the best of their musicianship to this performance, responding to the broad outline and the intimate details of Maestro Layton’s leadership with commitment. Mastery of Bach’s style is expected of an ensemble acclaimed for historically-appropriate playing, but the players of the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment confirm that they are not merely impeccably-trained musicians: in this performance of the Weihnachtsoratorium, they are fully-fledged participants in the drama, their individual and collective contributions combining with the solo and choral singing and Maestro Layton’s inspired leadership to weave from Bach’s musical threads an extraordinarily beautiful fabric.

Such admirable frames are so often spoiled by imperfect portraits by soloists, and an enormous debt of gratitude is owed to those who planned this recording for engaging a quartet of soloists among whom there is no disappointment. Though intermittently prone to turning slightly blowsy in the highest reaches of her music, the voice of soprano Katherine Watson shimmers attractively, particularly in the ‘echo’ aria ‘Flößt, mein Heiland, flößt dein Namen’ in Part Four. Ms. Watson handles ‘Nur ein Wink von seinen Händen’ in Part Six sensitively, and her contributions to the trio ‘Ach, wenn wird die Zeit erscheinen’ in Part Five are radiant. Matching Ms. Watson with rounded tones at the opposite end of the vocal spectrum is bass Matthew Brook. Starting with his singing of ‘Großer Herr, o starker König’ in Part One, Mr. Brook offers a charming, forthrightly-sung performance of the music for bass. The beautiful duet with soprano in Part Three, ‘Herr, dein Mitleid, dein Erbarmen,’ is sumptuously sung by both Ms. Watson and Mr. Brook, and the bass’s singing in the sublimely inventive scenes with chorus in Parts One and Four is aptly filled with wonderment. Mr. Brook’s voice is moderately stronger at the top of his range than at the bottom, but he approximates nothing in his negotiation of the music. The only possible criticism of Mr. Brook’s performance is that he is in Part Six a decidedly genial Herod, with little suggestion of ambiguous intent in his instructions that the Christ child be found so that he, too, might ‘worship’ him. Musically, though, Mr. Brook’s singing is consistently impressive. Of a quality that soars past even very fine performances on previous recordings of the Weihnachtsoratorium is the singing of countertenor Iestyn Davies. Taking the alto solos with a rare combination of stylishness, grace, and limpidly beautiful tone, Mr. Davies sings with complete command of the tessitura of his music. The ethereal sheen of Mr. Davies’s upper register is tremendously effective, as is the unaffected but poised manner in which he sings. Among performances of his arias that aim for the emotional hearts of the music and unfailingly find their marks, Mr. Davies’s singing of ‘Schlafe, mein Liebster, genieße der Ruh’ in Part Two—at nearly eleven minutes in duration, the most extended aria in the oratorio—is especially memorable. In fact, every moment of Mr. Davies’s performance is unforgettable: even in comparison with other recordings by this gifted young singer, who goes from strength to strength, thisWeihnachtsoratorium is an imposing achievement.

Any narrative, regardless of its subject, recounted as poignantly as by James Gilchrist’s Evangelist in this performance cannot fail to captivate the listener’s imagination. Bach’s telling of the Christmas story does not rely as greatly upon the Evangelist as do his Passion settings, but much of the cumulative impact of this performance of the Weihnachtsoratorium comes from Mr. Gilchrist’s soulful, sonorous singing. Mr. Gilchrist is one of the few tenors singing today for whom mastery of the treacherously high tessitura of Bach’s Evangelist rôles is second nature rather than a carefully-managed stunt, and the unstinting freedom with which his diamond-bright voice flows through the Evangelist’s recitatives is one of the supreme pleasures of this recording. Mr. Gilchrist proves equally adept at navigating the lower centers of vocal gravity in the tenor arias. The exhortation to the ‘shepherds abiding in the field’ in Part Two, ‘Frohe Hirten, eilt, ach eilet,’ is broadly sung, and the focus that Mr. Gilchrist brings to his singing of ‘Ich will nur dir zu Ehren leben’ in Part Four is hypnotic. ‘Nun mögt ihr stolzen Feinde schrecken’ in Part Six is also touchingly sung by Mr. Gilchrist. Both the Evangelist’s music and the tenor arias being sung by the same singer is not as unusual in performances of theWeihnachtsoratorium as in those of Bach’s Passions, but a performance as thoroughly distinguished as Mr. Gilchrist gives on this recording is rare in any repertory.

Bach’s Weihnachtsoratorium has fared better on records than many Baroque masterpieces, its discography preserving performances by most of the 20th and 21st Centuries’ finest Bach singers and conductors, as well as notable outings by singers for whom Bach’s music was atypical repertory. Just as there are in any generation great singers and great voices but only a minuscule population of artists in whom both distinctions are united, there are many performances of Bach’s music that either uphold high artistic standards or fully explore emotional niches but few that manage to accomplish both tasks with equal skill. This the present Hyperion recording achieves with unforced elegance and refinement. Scholarship joining hands with the timeless quest to reveal the deepest essence of a composer’s music, this performance seeks the truest power of art, the elusive ability to transcend all of the boundaries of politics, religions, and societies in a journey to the unguarded recesses of the human psyche. Whether the individual listener believes that it was a man, a Messiah, or a myth that was born in Bethlehem two millennia ago, this recording celebrates Bach’s message of rebirth and renewal in ways that need not be taken on faith.

Joseph Newsome

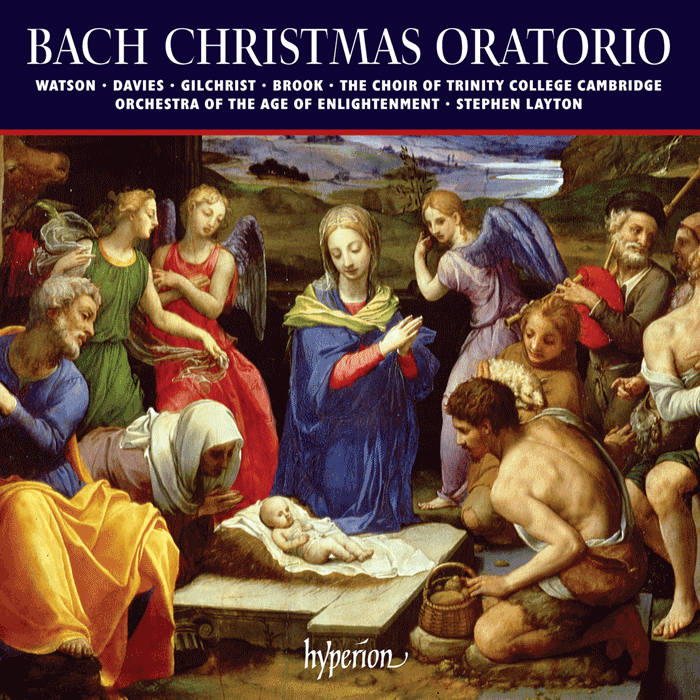

Hyperion Records CDA68031/2